IRI ENSO Forecast

IRI Technical ENSO Update

Published: August 18, 2017

Note: The SST anomalies cited below refer to the OISSTv2 SST data set, and not ERSSTv4. OISSTv2 is often used for real-time analysis and model initialization, while ERSSTv4 is used for retrospective official ENSO diagnosis because it is more homogeneous over time, allowing for more accurate comparisons among ENSO events that are years apart. During ENSO events, OISSTv2 often shows stronger anomalies than ERSSTv4, and during very strong events the two datasets may differ by as much as 0.5 C. Additionally, the ERSSTv4 may tend to be cooler than OISSTv2, because ERSSTv4 is expressed relative to a base period that is updated every 5 years, while the base period of OISSTv2 is updated every 10 years and so, half of the time, is based on a slightly older period and does not account as much for the slow warming trend in the tropical Pacific SST.

Recent and Current Conditions

In mid-August 2017, the NINO3.4 SST anomaly was in the middle of the ENSO-neutral category. For July the SST anomaly was 0.39 C, toward the warm side of ENSO-neutral, and for May-July it was 0.47 C, in the far upper part of the ENSO-neutral range. The IRI’s definition of El Niño, like NOAA/Climate Prediction Center’s, requires that the SST anomaly in the Nino3.4 region (5S-5N; 170W-120W) exceed 0.5 C. Similarly, for La Niña, the anomaly must be -0.5 C or less. The climatological probabilities for La Niña, neutral, and El Niño conditions vary seasonally, and are shown in a table at the bottom of this page for each 3-month season. The most recent weekly anomaly in the Nino3.4 region had cooled to -0.2, in the lower half of the ENSO-neutral range. The pertinent atmospheric variables, including the upper and lower level zonal wind anomalies, have been showing mainly neutral patterns. The Southern Oscillation Index (SOI) and the equatorial SOI have been near to somewhat above average. Subsurface temperature anomalies across the eastern equatorial Pacific have declined to become just slightly below average. The combination of the SST and the atmospheric conditions clearly warrants an ENSO-neutral diagnosis.

Expected Conditions

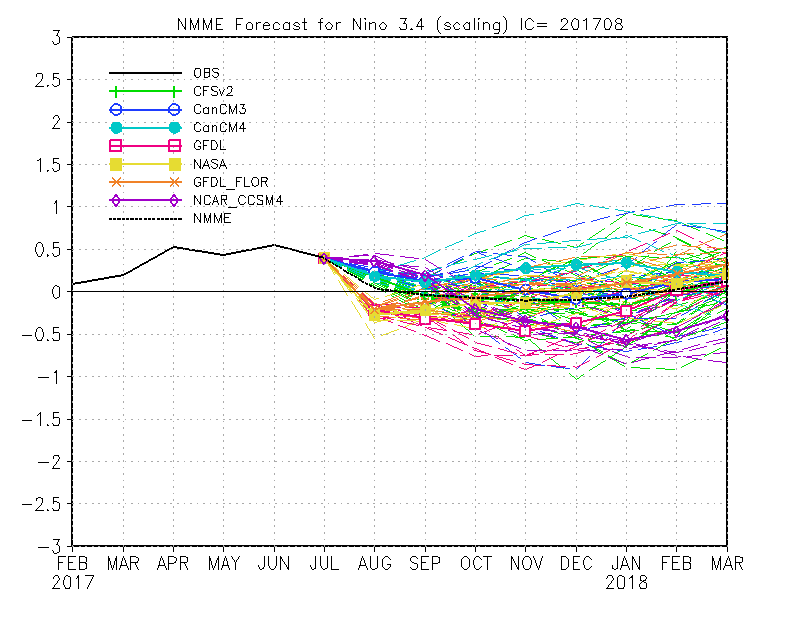

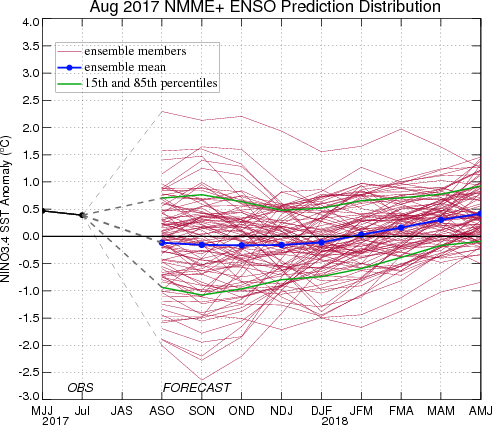

What is the outlook for the ENSO status going forward? The most recent official diagnosis and outlook was issued approximately one week ago in the NOAA/Climate Prediction Center ENSO Diagnostic Discussion, produced jointly by CPC and IRI; it stated that ENSO-neutral has the greatest chance of prevailing through fall and into winter, with markedly lower chances for El Niño or La Niña development. The latest set of model ENSO predictions, from mid-August, now available in the IRI/CPC ENSO prediction plume, is discussed below. Those predictions suggest that the SST has the greatest chance for being in the ENSO-neutral range for August-October through the rest of 2017, and show a likelihood of only 25% or less for El Niño development and for La Niña development through the period.

As of mid-August, at least 78% of the dynamical or statistical models predicts neutral ENSO conditions from the initial Aug-Oct 2017 season through the final Apr-Jun 2018 season. During this period, less than 10% of models predict El Niño conditions except for the final March-May and Apr-June 2018 seasons, when the percentage of models increases to about 20%. During this period, up to about 15% of models predict La Niña conditions, maximizing in the Dec-Feb season. At lead times of 3 or more months into the future, statistical and dynamical models that incorporate information about the ocean’s observed subsurface thermal structure generally exhibit higher predictive skill than those that do not. For the Nov-Jan 2017-18 season, among models that do use subsurface temperature information, 84% of models predicts neutral conditions, 11% predicts La Niña conditions, and 5% predicts El Niño conditions. These are similar percentages to those using all models, and the similarity persists also for longer lead target periods.

Note – Only models that produce a new ENSO prediction every month are included in the above statement.

Caution is advised in interpreting the distribution of model predictions as the actual probabilities. At longer leads, the skill of the models degrades, and skill uncertainty must be convolved with the uncertainties from initial conditions and differing model physics, leading to more climatological probabilities in the long-lead ENSO Outlook than might be suggested by the suite of models. Furthermore, the expected skill of one model versus another has not been established using uniform validation procedures, which may cause a difference in the true probability distribution from that taken verbatim from the raw model predictions.

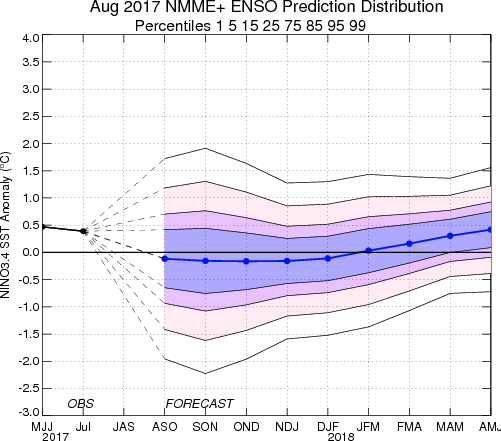

An alternative way to assess the probabilities of the three possible ENSO conditions is more quantitatively precise and less vulnerable to sampling errors than the categorical tallying method used above. This alternative method uses the mean of the predictions of all models on the plume, equally weighted, and constructs a standard error function centered on that mean. The standard error is Gaussian in shape, and has its width determined by an estimate of overall expected model skill for the season of the year and the lead time. Higher skill results in a relatively narrower error distribution, while low skill results in an error distribution with width approaching that of the historical observed distribution. This method shows probabilities for La Niña low throughout the forecast period, maximizing at about 25% during the Oct-Dec 2017 through Dec-Feb seasons. Similarly the chances for El Niño are low throughout, hovering just over 20% for fall 2017 and winter 2017-18, then rising to just over 30% by late spring 2018. Probabilities for ENSO-neutral are more than 80% for Aug-Oct, dropping to about 55% from Oct-Dec to Dec-Feb, and rising to about 65% for the final seasons of Feb-Apr through Apr-Jun 2018. Again, neutral is the clearly favored outcome. A plot of the probabilities generated from this most recent IRI/CPC ENSO prediction plume using the multi-model mean and the Gaussian standard error method summarizes the model consensus out to about 10 months into the future. The same cautions mentioned above for the distributional count of model predictions apply to this Gaussian standard error method of inferring probabilities, due to differing model biases and skills. In particular, this approach considers only the mean of the predictions, and not the total range across the models, nor the ensemble range within individual models.

In summary, the probabilities derived from the models on the IRI/CPC plume describe, on average, a preference for ENSO-neutral throughout the forecast period, with chances for El Niño or La Niña less than one-half those for neutral throughout. A caution regarding this latest set of model-based ENSO plume predictions, is that factors such as known specific model biases and recent changes that the models may have missed will be taken into account in the next official outlook to be generated and issued in early June by CPC and IRI, which will include some human judgement in combination with the model guidance.

Climatological Probabilities

| Season |

La Niña |

Neutral |

El Niño |

| DJF |

36% |

30% |

34% |

| JFM |

34% |

38% |

28% |

| FMA |

28% |

49% |

23% |

| MAM |

23% |

56% |

21% |

| AMJ |

21% |

58% |

21% |

| MJJ |

21% |

56% |

23% |

| JJA |

23% |

54% |

23% |

| JAS |

25% |

51% |

24% |

| ASO |

26% |

47% |

27% |

| SON |

29% |

39% |

32% |

| OND |

32% |

33% |

35% |

| NDJ |

35% |

29% |

36% |

IRI/CPC Mid-Month Model-Based ENSO Forecast Probabilities

| Season |

La Niña |

Neutral |

El Niño |

| ASO 2017 |

9% |

82% |

9% |

| SON 2017 |

19% |

65% |

16% |

| OND 2017 |

24% |

55% |

21% |

| NDJ 2017 |

25% |

54% |

21% |

| DJF 2018 |

24% |

55% |

21% |

| JFM 2018 |

17% |

61% |

22% |

| FMA 2018 |

10% |

67% |

23% |

| MAM 2018 |

6% |

68% |

26% |

| AMJ 2018 |

5% |

63% |

32% |