February Climate Briefing: El Tease-O

From the February climate briefing, given by IRI’s Chief Forecaster Tony Barnston:

Tony Barnston provides an overview of the briefing

Changes from last month’s briefing

Based on the latest models, the chance of an El Niño developing during the current (February – April) season is around 48%, down from 63% last month. These odds for the current season are down slightly from those issued by the NOAA Climate Prediction Center/IRI forecast on February 5.

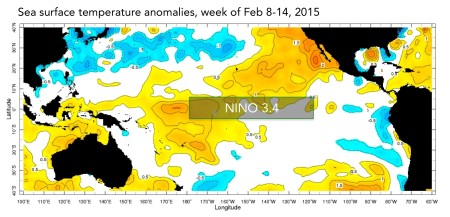

In the week leading up to the briefing, sea-surface temperatures (SSTs) in the Nino3.4 region (see image) were 0.5ºC above average. This is just at the threshold for El Niño conditions. The weekly temperature averages, however, are a relatively “instantaneous” measurement, so uncertainty about an El Niño event remains. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration will only declare an El Niño event if +0.5ºC SST conditions are sustained for the next two months.

With only one exception, weekly measurements of Nino3.4 SSTs have been at or above the 0.5ºC threshold since late October. The weekly temperatures haven’t exceeded a 1.0ºC anomaly, however, keeping the anomalies in a weak El Niño range.

Why no Niño?

Atmospheric conditions typically associated with El Niño have been largely absent. An El Niño event usually induces more cloudiness and rainfall than normal near the intersection of the international dateline and the equator, which is what scientists say leads El Niño to exert its climate impacts outside of the tropics. This convection has been mostly absent, but cloudy and rainy conditions have finally begun to appear in this region. The convection isn’t likely to have a lasting effect, though, because El Niño events typically terminate in Northern Hemisphere spring.

The IRI/CPC probabilistic ENSO forecast issued mid-February 2015. Note that bars indicate likelihood of El Niño occurring, not its potential strength. Unlike the official ENSO forecast issued at the beginning of each month, IRI and CPC issue this updated forecast based solely on model outputs. The official forecast, available at http://1.usa.gov/1j9gA8b, incorporates human judgement.

Nonetheless, most models are calling for Nino3.4 SST anomalies to remain above 0ºC for the rest of 2015, although we are approaching the “spring predictability barrier” through which it is more difficult for models to make good predictions. For what it’s worth, the dynamical models (those based on the physical laws governing our earth and atmosphere) predict a weak El Niño to form, while the statistical models predict warm but neutral ENSO conditions. Barnston says the divergence stems from the dynamical models more-sensitive-response to subsurface heating compared to statistical models, and we have new subsurface heat from a moderate westerly wind event during the last month. Statistical models usually use recent seasonal averages, so even if they incorporate subsurface temperatures, the new warmup below the surface would be averaged in with December and early January, damping the strength of the heating anomaly.

Effects of El Niño on global seasonal forecasts

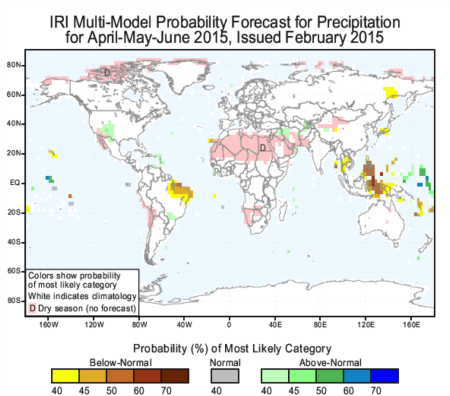

Each month, IRI issues seasonal climate forecasts for the entire globe. These forecasts take into account the latest ENSO SST projections and indicate which areas are more likely to see above or below normal temperatures and rainfall. For the April-June period, the forecast continues to show a strong likelihood of drier-than-normal conditions over Indonesia, and a moderate likelihood of dry weather in northern South America (image right). Wetter-than-average conditions are somewhat more likely in the southwestern United States.

Each month, IRI issues seasonal climate forecasts for the entire globe. These forecasts take into account the latest ENSO SST projections and indicate which areas are more likely to see above or below normal temperatures and rainfall. For the April-June period, the forecast continues to show a strong likelihood of drier-than-normal conditions over Indonesia, and a moderate likelihood of dry weather in northern South America (image right). Wetter-than-average conditions are somewhat more likely in the southwestern United States.

Barnston notes in the video above that with the exception of parts of Brazil, many of the areas forecasted to have a higher likelihood of above or below average rainfall haven’t seen the predictions play out. Since the seasonal forecasts are based on sea surface temperatures, lack of atmospheric participation in this ENSO event may be in part to blame for the reduced accuracy of the forecasts.

Learn more about El Niño on our ENSO resources page, and sign up here to get notified when the next forecast is issued. In the meantime, check out #IRIforecast or use #ENSOQandA on Twitter to ask your El Niño questions.

You must be logged in to post a comment.