Training the Agents of Change: A New Approach to Reach Ethiopia’s Climate-Vulnerable Farmers

Driving on a new, six-lane expressway, it takes about an hour and a half to get from Ethiopia’s capital, Addis Ababa, to the city of Adama, about 60 miles to the southeast. Around 300,000 of Ethiopia’s 100 million people live in Adama, and at its center it feels just as bustling as the nearby capital, even though the city sits in a region that is predominately agrarian.

A few blocks off of one of Adama’s main roads is an office of the Oromia Regional State’s Agriculture Bureau. It’s a small compound of single-story buildings that surround a dusty courtyard peppered with trees, trucks, tractors and scooters. Mekonnen Diriba has been an agronomist here for the last four years, advising surrounding farming communities on new and best practices in agriculture.

In October 2018, Diriba was one of 55 participants who completed a two-week training held in Addis Ababa on using new climate information products available online. The course, supported by ACToday—a Columbia World Project led by the International Research Institute for Climate and Society—was the first to bring personnel from district offices of the National Meteorological Agency as well as those from agriculture, health and disaster risk management agencies. The training marked the next major step for ACToday in Ethiopia, as the project aims to equip farmers with the best available climate information to manage their food production in times of drought and other climate extremes. Agronomists like Diriba play a key role in ensuring that this happens.

Mekonnen Diriba, agronomist, at his office, a zonal branch of the Oromia Regional State’s Agriculture Bureau.

Managing rainfall variability is the most important issue farmers face in Ethiopia, Diriba said. “Because the onset and ending of the rainy season are highly variable, this makes a big challenge for farmers to practice their normal agriculture.”

Ethiopia is still heavily reliant on smallholder farming, which accounts for 85% of the country’s employment and 95% of its agricultural production, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization. Most of the country’s 12 million farming households do not have access to irrigation, making the timing and amount of rains even more critical.

“In Ethiopia, which is frequented by drought, climate variability has drastic impacts on crop yields, which leads to lower incomes for farmers and less available food,” said IRI’s Tufa Dinku, who oversees ACToday efforts in Ethiopia. Dinku worked extensively with the Ethiopian government to bring together different government ministries for this training. “It’s only through trainings like these that we can solve the problem of how to get actionable climate information to those who need it to make decisions that can affect millions of people.”

This is what it will take for farmers to make climate-based decisions to help them grow more food – thousands of intermediaries with enough training and access to deliver the information to farmers in a usable format.

For a decade, Dinku has led IRI’s ENACTS initiative, which has been able to transform the quality and quantity of national climate data sets and derived information products in a dozen African countries, including Ethiopia. Helping create these new resources and making them available online was only the first step, said Dinku. Equally important is that these products be accessible and useful to individuals and institutions who make planning decisions about agriculture, public health, water and other climate-sensitive sectors.

That’s why he intentionally developed the two-week training for regional-level personnel. “The staff working in the country’s branch offices play a critical role. They’re closer to the actual users of climate information,” he said. “They understand their needs.”

For example, while employees at headquarter offices in Addis Ababa could brief the Ministry of Agriculture on a national-level overview, they are less likely to be up-to-date on farm-level issues, or to be able to tailor their advisories to millions of Ethiopian farmers.

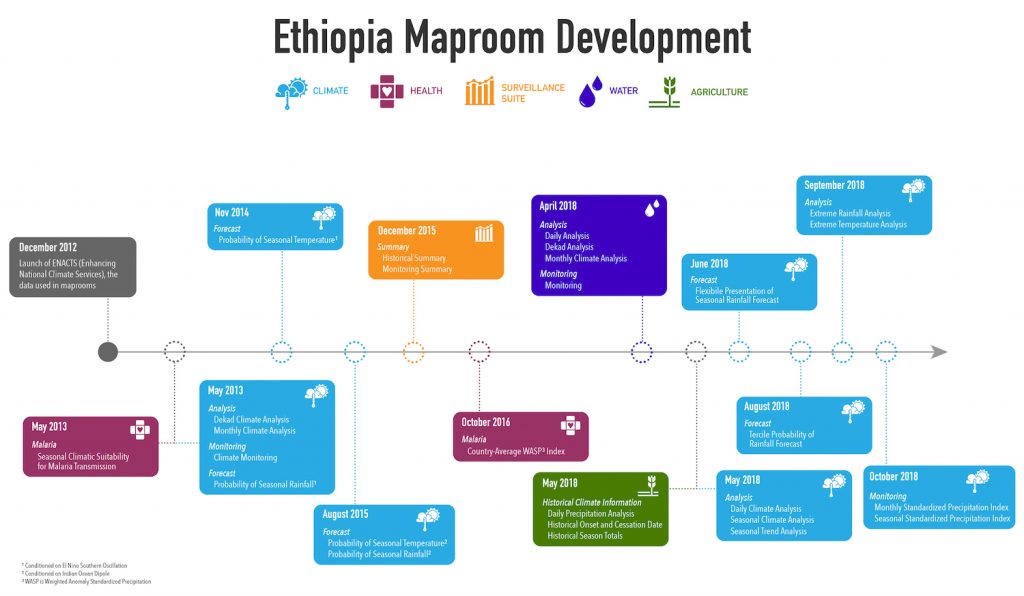

Ethiopia ENACTS Maproom Development

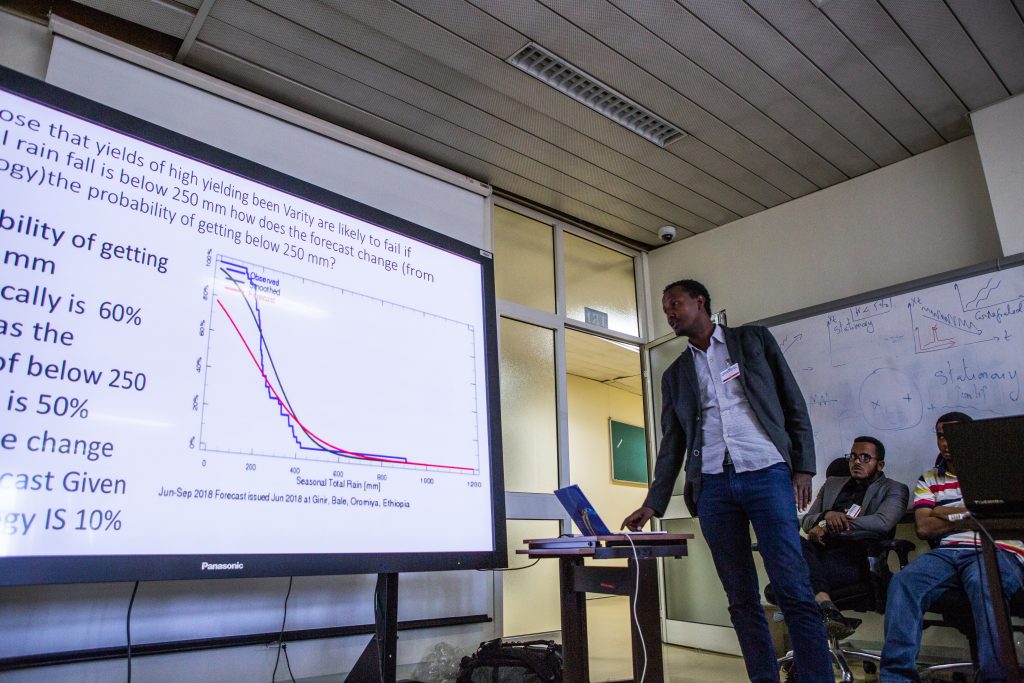

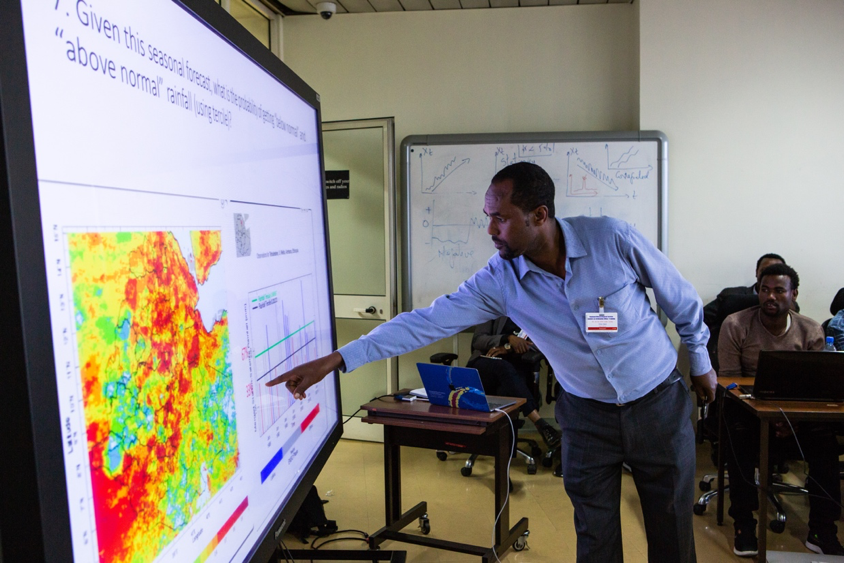

The participants received a week of instruction on fundamental climate science followed by a week on using maprooms—web-based interactive tools powered by IRI’s Data Library that allow users to find and interpret accurate, up-to-date climate information at the local level. One of the first goals of ACToday in Ethiopia has been to improve the maprooms’ data and user interface to make them more usable for non-scientists. The training introduced several new maps that build off of six years of work under the ENACTS initiative and offered a first opportunity to share the results more broadly. A dozen new maprooms have added information tailored for the water and agriculture sectors, as well as climate information of interest across sectors (see graphic). These maprooms in particular have been better tailored to the needs of the people who are going to use them, and they’ve since generated more demand. Participants immediately noted the profound changes the maprooms could make in their work.

The maprooms utilize historical data, monitoring data, statistical analyses and forecasting methods to provide climate information. For example, with one click a user can see how recent rainfall in their area compares to the last few years and to the long-term average. By monitoring a season’s rainfall as it goes along, there can be better real-time understanding of climate-related risks – for example, whether crops are likely to fail from lack of rainfall. A user can also see whether there’s an increased chance in the months ahead for below or above average rainfall. The maprooms are the only place where this kind of information is available together and without having to download data and run separate analyses.

With the maprooms, “now we can give any information about every point of the region. This will make our job easier.”

Wendesen Temesgen, from the Ethiopia National Meteorological Agency’s Southern Regional Service Center

Akoma Okugn attended as a representative from the Gambela Regional Health Bureau. With the maproom tools, he said, his office can now learn about potential droughts ahead of time and that food aid and nutrition assistance may be needed to help communities.

Maprooms also help climate experts from the Ethiopia’s weather service do their jobs faster and with more accuracy. Participant Wendesen Temesgen, from the National Meteorological Agency’s Southern Regional Service Center, develops climate bulletins for people working in health, agriculture and water management. “We have a variety of climates in this region,” he said. “We have some parts which receive rainfall almost 10 months of the year. Other parts receive a very small amount of rainfall for only few months.” The number and distribution of weather stations in the region is also uneven, he said, which has made it very difficult to give accurate information to decision makers in certain areas.

“The maprooms have solved this,” said Temesgen. “Now we can give any information about every point of the region. This will make our job easier.”

Eneye Assefa, a crop expert at the Amhara regional agriculture office, said she had no meteorological knowledge before the training. The training gave her more confidence to advise farmers on what crops to plant based on rainfall forecasts, with the goal of increasing their productivity.

Assefa planned to train her colleagues as well as those in administrative units below hers when she returned to her office. This is exactly what Dinku hoped would happen—that the participants go back to their respective regions and propagate the training and use of maprooms to other agronomists and agriculture extension professionals. And since many farmers don’t have direct internet access, this is what it will take for farmers to make climate-based decisions to help them grow more food – thousands of intermediaries with enough training and access to deliver the information to farmers in a usable format.

Small groups work on an exercise designed to apply the climate science and maproom knowledge taught during the training.

Small groups presented the results of the exercise to the full participant group.

Tufa Dinku listens to the group presentations.

Participants gather for the group presentations.

Mekonnen Diriba, foreground center, listens to the group presentations.

Eneye Assefa, third seated from left, speaks during the closing ceremony of the training.

Small groups presented the results of the exercise to the full participant group.

Next, Dinku says that the NMA and the other relevant ministries will need to plan and budget for more training on a wider scale. “The Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock has already indicated an interest to support training of users through its extension system,” he said. Other efforts will use events and meetings to raise awareness about the tools, and a training curriculum, manual and guide are being developed under ACToday to provide support for the trainings. There is also buy-in at the international level – the World Meteorological Organization’s Global Framework for Climate Services has indicated it could provide financial support.

The training ended in Addis Ababa on a Friday. The following Monday morning, Diriba presented what he learned to his regional office director, including his ideas for training people like the development agents who interact with farmers the most. The director approved his plan that day.

You must be logged in to post a comment.