October Climate Briefing: Teetering on La Niña

Read our ENSO Essentials & Impacts pages for more about El Niño.

Tony Barnston provides an overview of the briefing

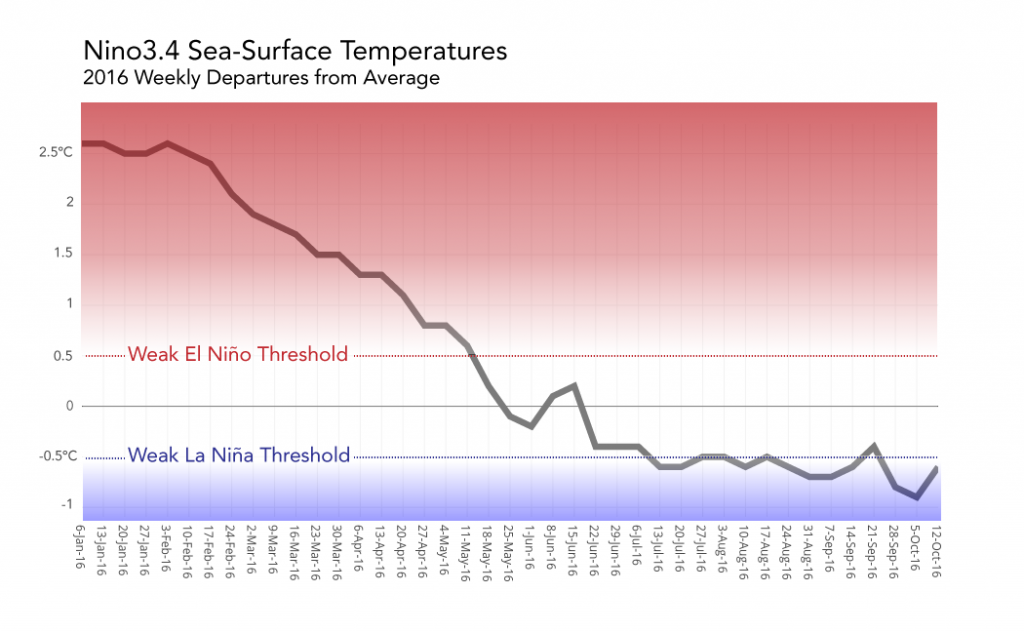

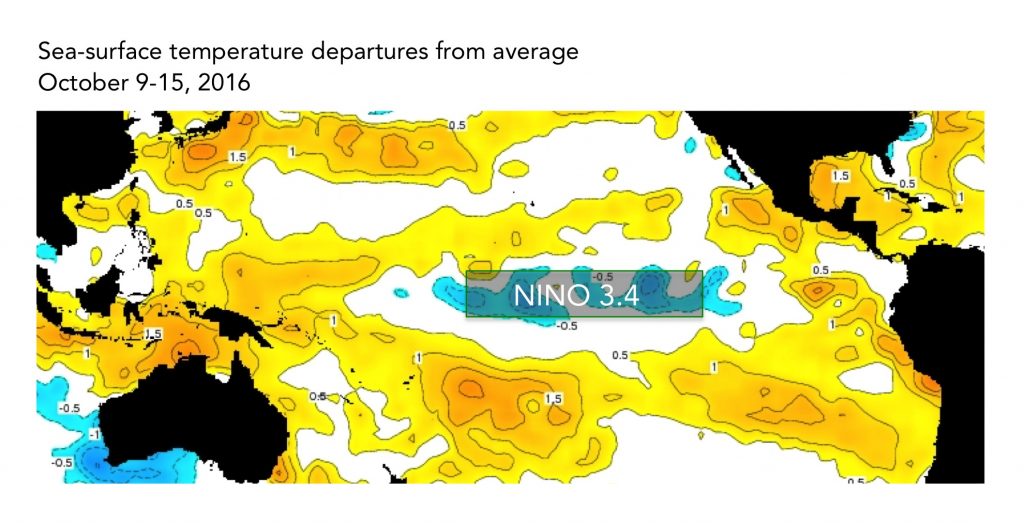

Sea-surface temperatures in the area of the central equatorial Pacific Ocean that define El Niño and La Niña events, called the Nino3.4 region, are slightly cooler than those in the weeks leading up to last month’s briefing. Since July, weekly sea-surface temperature anomalies have been around the -0.5º threshold used to define La Niña (see below images).

Although these sea-surface temperatures might seem to indicate a borderline La Niña event, the dual nature of La Niña events requires both the ocean and atmosphere to participate. While sea-surface temperatures should be cooler than normal, trade winds in the same area should be stronger than normal during a La Niña event. Since mid-September, trade winds in the western portion of the equatorial Pacific have picked up some, but the lack of basin-wide enhanced trade winds is still the component keeping the La Niña event from fully developing.

Weekly sea-surface temperature anomalies in the Nino3.4 region of the central equatorial Pacific Ocean. For reasons outlined in this NOAA blog post, comparison of SSTs between datasets should be cautious, largely due to variation in data collection methods and resolution of the datasets. The dataset used for this figure (called OISSTv2) is not the one used in NOAA’s records for official peak strength (called ERSSTv4), though OISSTv2 is the one used in initializing models. Image: IRI/Elisabeth Gawthrop

The sea-surface temperatures in the Nino3.4 region (approximated here) serve as a primary metric of El Niño and La Niña conditions. Data from the IRI Data Library. Image: IRI/Elisabeth Gawthrop

In June, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Climate Prediction Center issued a La Niña watch in anticipation of likely La Niña conditions. That watch was cancelled last month, when scientists thought it was less likely that a La Niña event would fully develop. But, since the middle of last month, indicators of La Niña-like sea-surface temperatures and trade winds again started to look more promising, and NOAA re-issued the watch. More details from NOAA’s ENSO blog.

For a La Niña event to officially be classified as such in the record books, NOAA requires five consecutive 3-month Nino3.4 averages of -0.5ºC or cooler. The July-August-September period came in at -0.5º, so a La Niña will technically occur if the next four seasonal periods are at least as cool, beginning with the August-September-October period that will end soon.

As we reported last month, some La Niña impacts are expected to occur regardless of whether a La Niña is officially declared; the -0.5ºC threshold is a guideline for impacts, but not an absolute.

To predict El Niño, computers model the SSTs in the Nino3.4 region over the next several months. The graph in the first image of the gallery shows the outputs of these models, some of which use equations based on our physical understanding of the system (called dynamical models), and some of which use statistics, based on the long record of historical observations.

The mean of the statistical models calls for SST conditions to gradually warm, reaching 0ºC in the March-April-May season. The mean of the dynamical models runs in parallel to the statistical models but about 0.25ºC cooler. All of the models follow this slow, overall warming trend, and the spread of the models is in the 1 to 1.5ºC range for most of the forecast period.

Based on these model outputs, chances for La Niña development in the current October-November-December 2016 are between 55% and 60%, up just a few points from last month’s model-based forecast. Odds for La Niña quickly decline in the following seasons, with neutral conditions dominating in the new year (see third graph in gallery above).

The probabilistic forecast issued by CPC and IRI in early October shows higher odds for La Niña conditions. This early-October forecast uses human judgement in addition to model output, while the mid-October forecast relies solely on model output.

Effects of El Niño on global seasonal forecasts

Each month, IRI issues seasonal climate forecasts for the entire globe. These forecasts take into account the latest sea-surface temperature projections and indicate which areas are more likely to see above- or below-normal temperatures and rainfall.

For the upcoming November-January period, the forecast shows moderate likelihood of drier-than-normal conditions over the southeastern United States, southeast South America and parts of eastern Asia (first image in gallery above, click to enlarge). There is also some likelihood of drier-than-normal conditions in eastern equatorial Africa, central southwest Asia, and central Australia.

The November-January forecast also shows a strong chance of above-average precipitation in some areas of Indonesia and the Philippines. Other regions with an elevated chance of above-average precipitation include northern South America, southern Africa and the northwestern United States.

El Niño in context: Resource page on climate variability

The impacts listed above are specifically for the November-January season. For later seasons, see forecast maps in the image gallery and on our seasonal forecast page.

Learn more about La Niña on our ENSO resources page, and sign up here to get notified when the next forecast is issued. In the meantime, check out #IRIforecast or use #ENSOQandA on Twitter to ask your La Niña questions.

You must be logged in to post a comment.