NASA and IRI: Bringing ‘Space to Village’ in East Africa

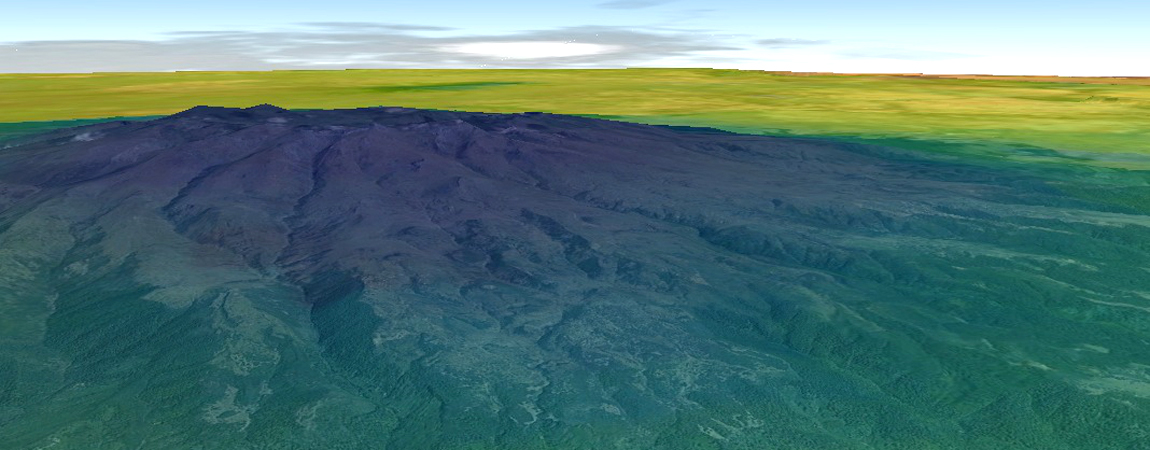

NASA Landsat image of Mount Elgon and the adjacent Great Rift Valley in Kenya, overlaid with minimum land surface temperatures to illustrate how temperature changes with elevation.

IRI and NASA have been working together for the past five years on developing products derived from remotely sensed images for monitoring climate and environmental factors that affect the transmission of vector-borne diseases. Their collaboration has expanded recently through new activities with SERVIR Africa, NASA’s partnership with the U.S. Agency for International Development and the Regional Centre for Mapping of Resources for Development (RCMRD) in Eastern Africa. In June, IRI ran a workshop in Nairobi, Kenya, organized by RCMRD, the World Health Organization’s Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases and the International Development Research Centre to bring together social and natural scientists interested in incorporating satellite and climate data into vector-borne disease research.

“New developments in satellite imagery have allowed us to learn more about the impact environmental variables have on the spread of vector-borne diseases,” says Pietro Ceccato, a remote-sensing specialist at IRI, referring to the mosquito “vectors” that carry and transmit malaria and other potentially fatal diseases.

Many factors determine whether, where and when vector-borne disease outbreaks occur, but the scientists all agreed that in some geographic areas, climate is one of the main drivers.

For instance, temperature not only impacts the development of the Plasmodium parasite that causes malaria, but it also regulates the development of the Anopheles mosquitos that carry and transmit it to humans. Warming in the East African highlands as a result of climate change is a major concern for the spread of malaria and other vector-borne diseases to areas previously too cold for disease transmission to occur. The current extensive drought in East Africa also has implications for changes in vector species, human-vector interactions and disease outbreaks. Post-drought epidemics in particular are a public health challenge, as a population’s immunity will decline during periods of low transmission.

For more than a decade, Ceccato has been working to develop new methods of manipulating data from different NASA satellites for the detection of water bodies and climate variables such as temperature and precipitation.

Data from NASA’s polar orbiting satellites are free of charge and provide a reliable, routinely updated and geographically thorough data source to study the relationship between climate and disease, even in the most remote regions in Africa.

Although satellite data can lead to a greater knowledge of the physical relationship between climate and disease, IRI’s partnership with NASA goes way beyond the development of data products.

“At SERVIR Africa, we recognize the need to engage stakeholders across the research practitioner divide in order to ensure our data products support decision making across various disciplines impacted by climate change,” says Andre Kooiman, SERVIR East Africa Regional Director. “IRI is uniquely placed in its capacity to help us achieve these objectives.”

Engaging both social and natural scientists through research capacity building workshops and talking directly to policy makers and practitioners about their information needs is key to bringing to the science of space to vulnerable African villages.

You must be logged in to post a comment.