World Meteorological Day 2018: Zika Update

In conjunction with World Meteorological Day, the World Meteorological Organization has released its “State of the Climate Global 2017” report. It was a record-setting year in terms of the costs of extreme events, which included the hurricanes in the North Atlantic, monsoon flooding on the Indian subcontinent and drought in parts of eastern Africa. The year was also the hottest one that wasn’t given an added temperature boost from El Niño.

The report ends with an update on the latest research on climate and Zika virus, co-authored by IRI’s Ángel Muñoz and Madeleine Thomson, along with partners from the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, Upstate Medical University and the World Meteorological Organization.

The Zika virus update notes that while neither El Niño or climate change are solely to blame for the recent epidemic in Latin America and the Caribbean, they were contributing factors. The latest research shows promise in using seasonal climate forecasts, combined with other methods, to predict areas at risk of an outbreak.

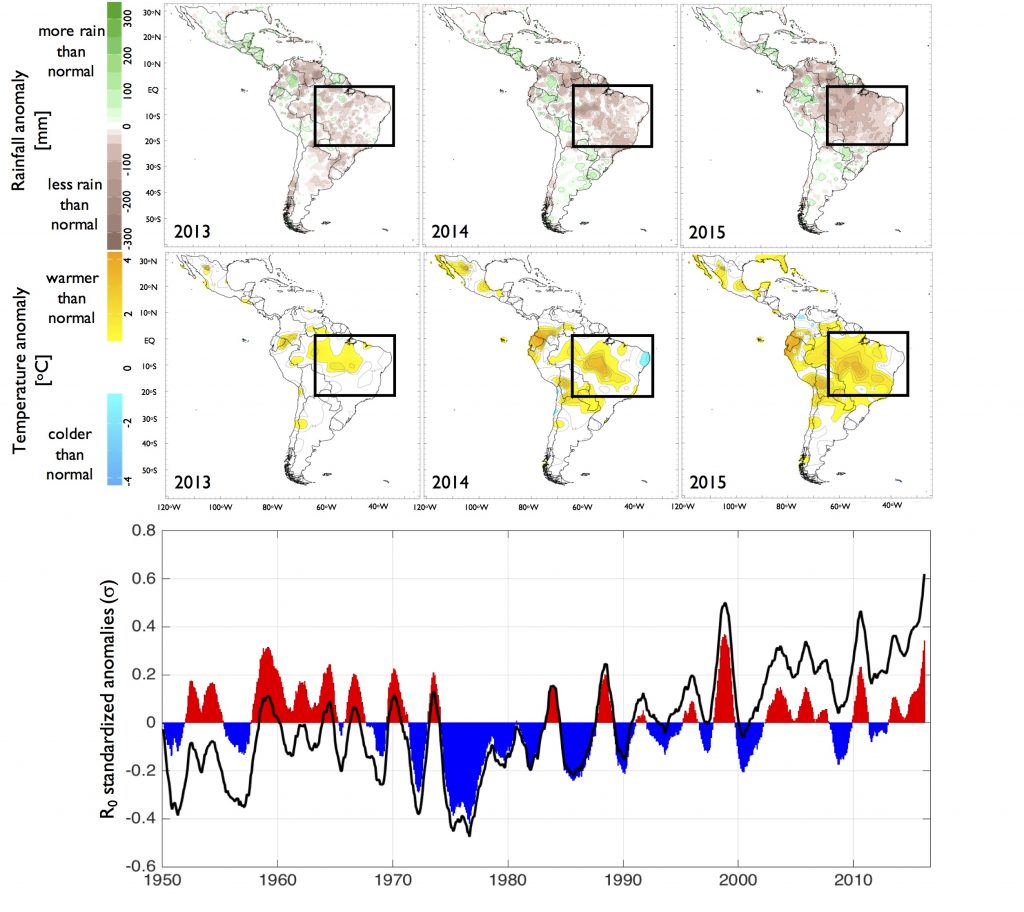

Annual rainfall anomalies (top panel) and temperature anomalies (middle panel) in 2013, 2014 and 2015; anomalies are computed with respect to the climatological period 1981–2010. Standardized anomalies of R0 (bottom panel; units in standard deviations). The total potential risk of transmission (black curve) shows an upward trend consistent with climate warming and cannot be explained only by the contribution of El Niño and other year-to-year climate modes (filled curve): a combination of climate signals has been driving the risk of transmission in the region. Black boxes indicate the sector of analysis (after Muñoz et al., 2016b, 2017 as cited in report).

“The Zika virus outbreak pushed us to build on previous research of other vector-borne diseases to quickly generate, translate, implement and start using tailored climate information with institutions like the World Health Organization/Pan-American Health Organization, the CDC’s Center of Excellence in the Northeast and so many other institutes in Latin America and the Caribbean,” said Muñoz.

Muñoz also said that the state-of-the-art forecasts continuously produced by the North American Multi-Model Ensemble (NMME) have been essential for the development of this new experimental prediction system, which includes diseases like Zika, dengue, chikungunya and yellow fever.

The above figure, from the report, is an example of how climate information can be translated into variables that decision makers, in this case health practitioners, can use in their field.

Find the full report here.

Additional reading on climate and Zika virus

Climate Remains a Question in Zika Virus Spread

As Congress dithers on Zika, climate signals get stronger (ClimateWire)

You must be logged in to post a comment.