Public Health in a Climate Context

To create and implement scientific solutions to climate change, we need a new generation of health professionals trained in the connection between climate and human health. A global consortium on climate and health education hosted by Columbia’s International Research Institute for Climate and Society and Mailman School of Public Health will discuss the best scientific and educational practices as well as model curricula at a meeting starting this week.

Recent scholarship has shown that policies addressing climate change can also bring benefits for public health. Commuting by bicycle, for example, not only reduces greenhouse gas and air pollution emissions, but it improves the rider’s heart health. Similarly, eating less red meat can reduce a person’s risk for heart disease and cancer and help reduce global warming, because meat production requires far more water and land resources than other forms of nutrition.

Madeleine Thomson, a senior research scientist at the International Research Institute for Climate and Society, is an expert on the relationship between climate variability and health. Patrick Kinney, professor of environmental health sciences at the Mailman School of Public Health, who has done pioneering research on climate change and urban smog, is director of a new program in climate and health.

Here, they discuss the symbiotic relationship between climate and health.

Five Questions with Madeleine Thomson

Q. What are some of the ways climate affects public health?

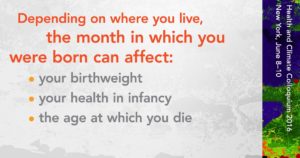

Climate predominantly affects poor populations in rural areas who do not have the capacity to protect themselves from their environment or smooth the disruptions to their health and livelihood brought about by seasonal changes and climate shocks. There also are less obvious effects. Birthweight, for example, is the single most important determinant of infant mortality and healthy development of children. In many parts of the world birth weight varies significantly by season, especially in regions that depend on rain-fed rather than irrigated agriculture. The period between planting and harvesting in these regions is widely known as the “hungry season.” During this time, women of reproductive age—including pregnant and lactating women—often have reduced nutritional intake and higher rates of water-borne diseases that affect fetal and early childhood development.

Q. How does the impact of long-term climate change compare with the effects of seasonal fluctuations in rainfall and extreme weather?

Many more people suffer from seasonal hunger than from dramatic famines, such as the one that affected 13 million people in the Horn of Africa in 2011. Long-term trends in climate have many and varied effects on health that are not easy to predict and can come through indirect routes such as the impact of climate on local and national economies and migration. Others will be more direct, involving changes in the distribution of certain diseases, reductions in food supply in areas of the world that are already food insecure, or as a result of an increase hydro-meteorological disasters such as droughts, floods or heat waves.

Q. Which countries see the harshest effects of climate change?

In developed countries we protect ourselves from the climate in numerous ways. We have well-built houses with insulation and air conditioning, early warning systems for floods and hurricanes, well-funded programs and health services that deal effectively with the prevention and management of climate-sensitive diseases. All of these may be lacking in developing countries, which are often in the tropics. Hot and humid climates are particularly favorable to vector-borne and water-borne diseases that thrive in poor environments.

Q. How does climate affect the spread of the Zika virus and other diseases?

Climate is an important driver of Zika virus transmission. High rainfall may result in an increase in outdoor breeding sites for the mosquitos that are Zika vectors, while drought years may result in increased water storage, and thereby increase mosquito-breeding sites. Warming temperatures also increase the development rates of both vector and virus. Zika was introduced and has spread in Latin America during a period of prolonged drought and at a time when the region’s temperature has been anomalously warm –2014 and 2015 were the warmest years on record until now —a result of both overall warming trends and the strong 2015-2016 El Niño.

Q. What are some other public health issues involving climate?

Climate’s impact both on agricultural productivity and food-supply chains affects the quality and price of staples and other basic foods essential for good nutrition. Price increases force the poor to make choices that often include the elimination of more expensive, more nutritious foods. More than a billion people are affected by malnutrition – both by stunted growth and obesity. Many also suffer the less obvious impact of micro-nutrient deficiencies; for example, they lack iron or zinc, resulting in weak immune systems and anemia. And of course all forms of malnutrition make individuals more susceptible to ill health – whether from infectious or non-communicable diseases. The health-care community is waking up to the risks that climate change poses to health. However, before considering what we might do to prevent climate-sensitive health outcomes in the future it is essential to better manage those of today. Climate will continue to raise public health concerns long into the future. The time to start to better manage such risks is now — climate information can be used as a resource in this process.

Five Questions with Patrick Kinney

Q. What is the biggest issue in the way climate affects public health? Is there something that keeps you up at night?

Right now, the largest risks to health have to do with extremes of climate – big coastal storms, like Katrina or Sandy, or periods of unusually hot weather, like the deadly European heat wave of 2003, which caused about 35,000 deaths. Climate change is making these events more extreme – that is, outside of our historical experience and ability to easily prepare for and rebound from. Over the long run, these risks will increase as we experience wider swings in the climate from year to year, week to week and day to day. In addition, climate change will lead to longer and more severe droughts in some regions, leading to crop failures and famine.

Q. How do these issues differ in developing countries versus the developed world?

While all countries will be affected, the impacts will likely be much greater in developing countries, due to their more limited resources and greater dependence on local climate for livelihoods.

Q. Can our public health systems cope with the challenge?

In developed countries, coping should be possible, although there is a need for training public health professionals. Health systems in developing countries already are under stress and climate change will exacerbate those stresses.

Public health research plays a key role in identifying and quantifying current risks and in estimating future impacts in a changing climate. This is critical for adaptation planning, so that new investments in resilience can be directed where they can have the most impact.

Q. It has been said that solving the climate crisis could reap huge benefits for public health. Can you explain?

One of the most important insights to emerge from recent scholarship has been the realization that policies to address climatic change can bring simultaneous benefits for human health. For example, commuting by bike instead of car reduces greenhouse gas and air pollution emissions while improving heart health. Eating a diet lower in red meat also brings huge personal health benefits as well as reducing methane emissions from livestock production.

Q. Much of your research has been on the effects of air quality on public health. How does that relate to climate?

Climate and air quality are intimately connected, and policies to address these twin challenges should be developed in a coordinated way. Many of the same fossil fuel burning sources that are responsible for climate change also put out pollutants that are directly harmful to human health. And as the climate changes, so, too, do patterns of air quality. Much of current research is focused on understanding how to capitalize on the opportunities to address both problems simultaneously.

You must be logged in to post a comment.