Climate Models and Food Security in the Philippines

By Megan Helseth

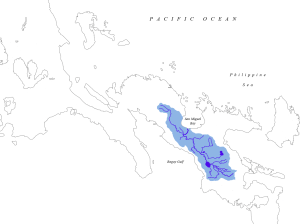

Drainage area of the Bicol River. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

The Bicol River Basin in the eastern Philippines is home to more than 5 million people, most of whom rely on agriculture and fishing for their livelihoods. The area is vulnerable to many climate and weather events, including typhoons, floods and dry spells. Each of these can have major impacts on local agriculture, and the strong 2015-16 El Niño intensified drought conditions in the region, while tropical cyclones caused flooding in certain locations. These impacts as well as those from long-term climate change pose uncertainty in the region’s agriculture sector. The development of accurate models that can forecast weather trends and water availability are becoming a key component in climate-related decision making that could impact the majority of Bicol residents’ food and economic security.

Starting in 2012, IRI partnered with the University of the Philippines Los Baños, the country’s Department of Agriculture and the Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration to tackle these climate-related challenges with the aim of improving water and food security in a region plagued by extreme weather. Central Bicol State University of Agriculture, Bicol University as well as local provincial governments and irrigators associations are also collaborating on the project, which is being supported by the US Agency for International Development. Food security is a particularly complex issue, as productive agriculture relies on favorable weather conditions and enough available water to sustain growing crops. The project aims to develop, test and apply decision-support tools for water use and allocation in the Buhi-Barit and Quinale A watersheds, and provide clear information about water availability in the region to farmers and local water managers.

Models developed by the IRI rely on climate and local hydrological data, and can calculate water supply available to users in the watershed. Understanding this data can help users understand how potential water availability will affect crop choices, for example, and make sure all farms receive their share of water.

But simply designing these models isn’t enough to ensure proper water management in the region.

On the ground, nearly 900 farmers have already attended 14 Climate Field Schools, where they learned how to use climate forecast and water availability information provided by the IRI. Project partners plan to run additional field schools in 2016.

An agricultural technician talks about integrated pest management to farmers at a climate field school in the Philippines.

While farmers are trained by local partners how to use the available climate information, the IRI is working closely with stakeholders to design-decision support tools that link water availability information and climate information to make detailed maps that help local stakeholders understand the possible outcomes of proposed plans. Refining these tools remains a part of the project, which runs through 2017. Additionally, working to integrate these tools into regular risk-management strategies–a shared responsibility among local irrigation specialists, hydropower managers, fishery managers and farmers–is key to the project’s success.

The project has involved a number of researchers and staff from IRI. Brad Lyon worked with PAGASA on a climate analysis that ultimately led to improved forecasts for the region. This improved climate information allowed Amor Ines and Eunjin Han to develop more sophisticated agricultural crop models that take into account expected climate conditions. Han, Kye Baraong and Erica Allis worked on a water management and allocation model for the Quinali A and Buhi-Barit watersheds. The information and outputs from all these activities are served via the IRI Data Library through a custom map room developed by Rémi Cousin.

The Bicol Agri-Water Project is working to develop, test, and apply agro-climate tools to support decisions for managing climate risks at the farm level and for managing water resources at the watershed level. This is a screenshot of the custom map room IRI developed with partners for the project.

“This project is an example of an integrated approach to climate risk management,” says Ines, the project’s principal scientist, now at Michigan State University. “Multiple actors – academics, policy makers, local government units, NGOs and farmers came together to address the challenges posed by climate change and variability to agriculture and water management.”

Increasing resiliency among populations vulnerable to growing climate risks is a challenging task, requiring dedication from a wide range of stakeholders to ensure risk management is integrated at all decision levels—from farmers deciding which crops to use each year to local water managers deciding how to allot resources.

Megan Helseth is completing her Master’s in Climate and Society at Columbia University. She is interested in long-term strategies for fighting and adapting to climate change, resource management strategies, and the politics of sustainability.

You must be logged in to post a comment.