Field Notes: Climate, Health and the Maasai

IRI’s Pietro Ceccato recently attended the 2nd Capacity Building Workshop for the World Health Organization TDR/IDRC research initiative on Population Health Vulnerabilities to Vector-Borne Diseases: Increasing Resilience under Climate Change Conditions in Africa, held at the Nelson Mandela University in Arusha, Tanzania. He shares his observations here.

John Hargrove, an entomologist based in South Africa, providing expertise on tsetse fly. Photo by Pietro Ceccato.

Earlier this year, I attended a workshop in Arusha, Tanzania to train research scientists from South Africa, Ivory Coast, Mauritania, Botswana, Kenya and Tanzania on how to use products derived from NASA satellites to monitor climate and environmental factors that influence the transmission of vector-borne diseases such as malaria, leishmaniasis, trypanosomiasis, schistosomiasis and Rift Valley Fever. Together, these diseases represent a scourge to both humans and animals in the region, affecting millions in East Africa alone.

At the workshop, I showed my colleagues how to access real-time images captured by NASA sensors such as TRMM, MODIS, LANDSAT to monitor precipitation, temperature, vegetation and water bodies. These environmental factors influence the reproduction of mosquitoes, tsetse flies and sand flies, which are vectors for the diseases I mentioned above.

Maasai village in Tanzania affected by trypanosomiasis. Photo by Pietro Ceccato.

For example, using this type of information, my team has discovered that flood conditions in the April-May-June season in South Sudan will reduce sandfly activity and therefore the transmission of leishmaniasis from September to November.

In collaboration with John Hargrove and his team from South Africa, I’ve been studying the impact of environmental conditions on the reproductive cycle of the tsetse fly and how the information can be accessed by local communities in real time to take actions to control trypanosomiasis transmission to the cattle and humans.

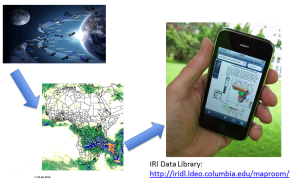

Dissemination of global satellite information to local communities.

During a field visit to a Maasai village two hours’ drive from Arusha, I was fascinated by the behavior of the chief, who was constantly on his mobile phone, connecting to people in the area. The access and use of mobile technology by this Maasai chief in such a remote area made me think about the possibility of delivering real-time information derived from NASA sensors directly to people’s cell phones there, so they can be alerted to areas and periods when there is a higher risk of trypanosomiasis transmission.

Using the IRI Data Library’s Maproom interface, anybody can access NASA products via smartphone. The chief of the Maasai village will be able to now get the location of pastures, water bodies, rainfall and temperature conditions —all factors in the transmission of the trypanosomiasis–in real time. Our next challenge will be to train these villagers on how to use these products for control measures!

You must be logged in to post a comment.